“Working Hard Every Day to Create That Brilliance”: The Women Goldbeaters Making History in Japan

A normal day for Naomi Takata might begin by getting persimmon juice to soak paper in. Elsewhere in the city, meanwhile, Mio Oketani might be starting her morning at another artisan’s workshop by painstakingly gathering up gold dust so that none of the precious substance will go to waste. The two are part of WMF’s Gold Leaf Production Craftsmanship Inheritance Program in Kanazawa, Japan, and since the traineeship’s launch in April 2022, they and the other six members of their cohort have been diligently working to acquire the core skills of the craft, which was added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2020. With a dwindling number of expert practitioners, mostly advanced in age, the tradition faces an uncertain future unless a new generation steps up to keep it alive.

The program, jointly conceived with Tiffany & Co., marks the first time WMF has undertaken a capacity-building project in Japan in the organization’s 20 years of work in the country. But the participation of Takata and Oketani is particularly newsworthy. While female family members of Kanazawa’s gold-leaf artisans have long participated informally in the craft, their contributions have often gone unrecognized, and no woman has ever been admitted in the Society for the Preservation of Traditional Kanazawa Gold Leaf (SPTKGL). If the two trainees are admitted into the professional organization following the completion of their training, it would mark a first in the craft’s long history. We spoke to the two of them about their motivations, their experience so far, and their aims for the future of women’s inclusion in traditional arts. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

WMF: What inspired you to apply for this program in the first place?

Naomi Takata (NT): I had previously worked at a company that handles gold leaf; I quit that job due to a health condition, but I could not forget the beautiful sheen and wanted to be involved with gold leaf again.

Mio Oketani (MO): I studied art and humanities in high school and college with a focus on Japanese traditional painting. As I was creating and viewing artwork, I felt a deep connection with gold leaf, so when I found out about this training program, I was motivated to become a gold leaf craftworker who could support the creative activities of artists and other creators.

WMF: Describe a typical day in the workshop. What does your schedule look like as a trainee?

NT: The routine depends on the monthly orders received by the studio. A day working to make the paper used in the process of beating gold leaf, for example, starts in the morning: we prepare a mixture of lye, persimmon juice, egg, and egg yolk, and then soak a bundle of paper in the mixture. We leave it for three hours and then wring out the bundles. We repeat this process in the afternoon; the next day, after the bundles have absorbed enough of the mixture, they are wrung out again and dried completely. The process of preparing this special paper is called kami-shikomi.

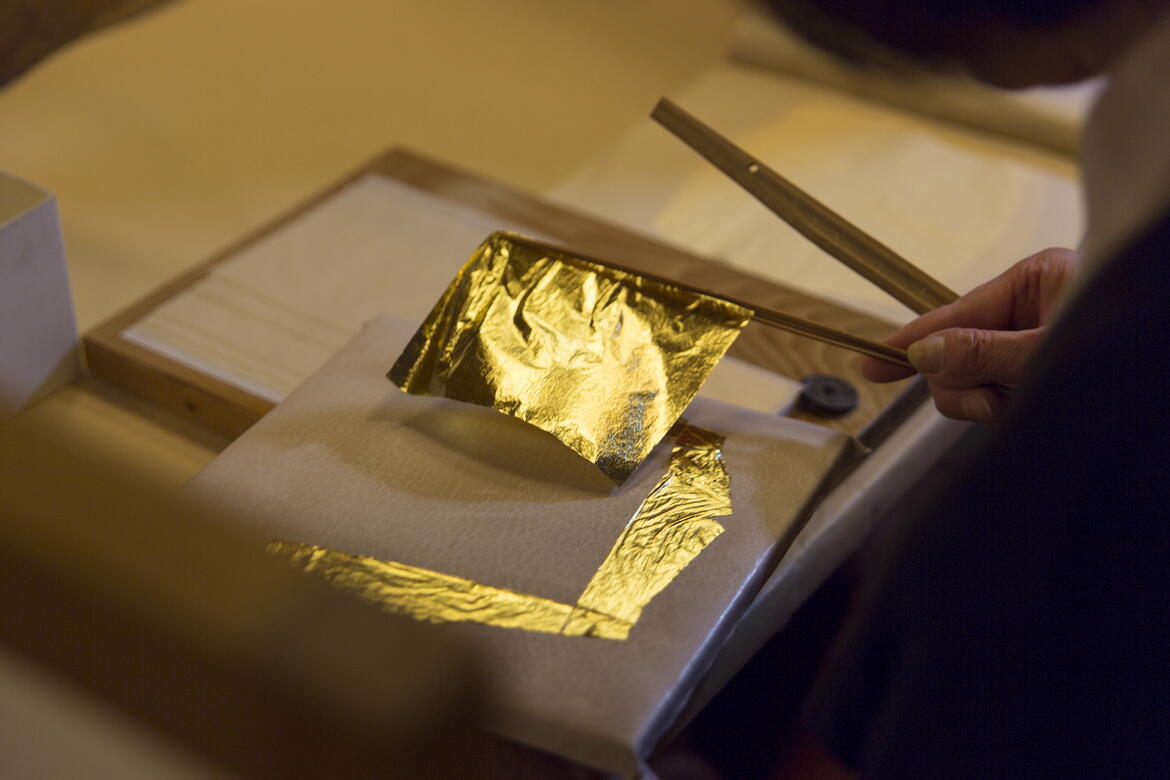

MO: The main daily tasks include trimming, bundling, and molding gold leaf, as well as removing any gold dust remaining on used gold-beating paper. I often spend all day doing the same task—for example, trimming from 9:00 to 16:00.

WMF: What is the most challenging aspect of the craft that you have encountered so far?

NT: Everything is hard—especially the process of pounding a bundle of lye-treated paper with a mechanized hammer until the sheets don’t stick together, or sorting paper by quality.

MO: From a beginner’s viewpoint, any job looks very difficult. Tasks involved in kami-shikomi that require sensory and empirical judgment take a long time to master. But since it’s an essential skill in gold leaf craftwork, I would like to work hard to master it. I’m getting used to it little by little, and it feels rewarding.

WMF: Has doing hands-on work given you greater appreciation for gold-leaf products and other crafts?

NT: Yes, it has. It takes endless steps to make gold leaf, and many materials are needed—paper, rice straw, persimmons, bamboo.

MO: I always thought that this was a tradition that should be passed on to future generations, and actually doing it makes me feel that this is very true. Once I have acquired the skills, I have a mission to train successors. I’ve started to think about what it takes to teach new apprentices.

WMF: What was the most surprising thing about learning these skills?

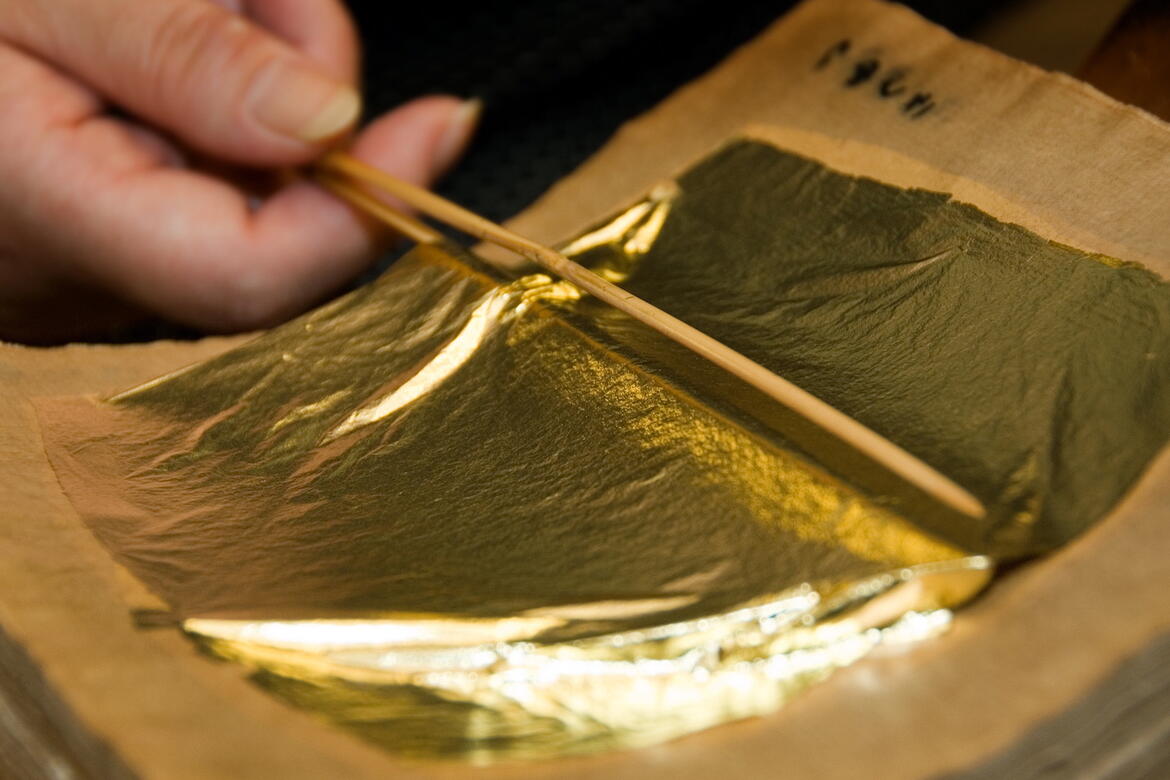

NT: I’m surprised at how long it takes to make one roll of gold-beating paper. The only part that involves a machine is pounding the paper. I think the charm of this handwork is that the finish of Kanazawa gold leaf is different every time.

MO: I thought I knew the process of manufacturing gold leaf, but it wasn't until I actually tried it that I realized what it takes. The effort and skills of many people are required, including the makers of traditional Japanese paper; zumi-ya, or craftsworkers who process the gold to a thickness of one thousandth of a millimeter; haku-ya, craftsworkers who hammer that down to one ten-thousandth of a millimeter in thickness; and others who secure raw materials and tools. A diverse group of people working hard every day to create that brilliance: this is the appeal of traditional Kanazawa gold leaf.

WMF: What do you think is the significance of your status as two of the first women to train in the craft of Kanazawa gold leaf production?

NT: If it's proven that women can do it too, the next generation will be inspired to try it as well.

MO: Many gold-leaf craftsmen are in their old age, and this makes it hard for younger generations to get into the field. I hope that we can work together with other young craftspeople and create a system that accepts trainees regardless of gender.