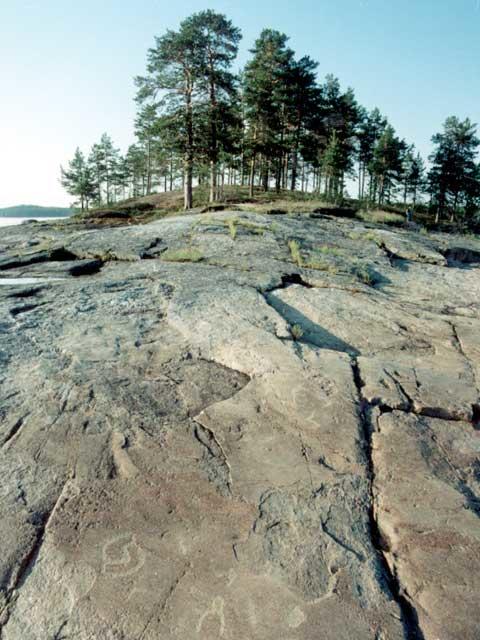

Karelian Petroglyphs

2002 World Monuments Watch

Considered among the most complex and expressive examples of rock art in northern Europe, the petroglyphs of the Karelian Republic include elaborate scenes of warfare, religious ritual, seafaring, and even skiing, carved into the red granite of the White Sea coast, and enigmatic and fantastic figures incised in rock on the shores of Lake Onega, 325 kilometers to the south. More than 70 ancient settlements have been identified in association with the White Sea carvings. Collectively, they constitute the largest Neolithic site in the region. While comparable petroglyph sites are known in Norway and Sweden, the Karelian petroglyphs are the only major rock art sites associated with the Ugro-Finnic peoples. In the nineteenth century, local monks, offended by the “obscenity” of the Lake Onega figures, altered them by “adding” strategically placed religious symbols. Human activity remains the biggest threat to the petroglyphs, which have been defaced with graffiti and scorched by campfires since the sites were reopened to the general public in 1992–1993. Changes in seawater chemistry, resulting from new hydroelectric power stations in the area, have contributed to the erosion of the White Sea carvings, while lichen growth has resulted in considerable damage to sites around Lake Onega. A lack of understanding of the importance of rock art among local residents, compounded with a lack of resources and training on behalf of the officials overseeing the sites, puts the Karelian petroglyphs at serious risk.

Since the Watch

Discoveries made in 2008 and 2009 have added to the inventory of petroglyphs around Lake Onega. Archaeologists from nearby Petrozavodsk State University speculate that the newly found petroglyphs, which include depictions of the Sun and the Moon, may mark the site of an ancient observatory. January 2011