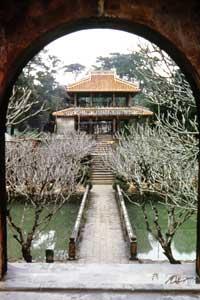

King Minh Mang, the second ruler of the Nguyen Dynasty, governed southern and central Vietnam from 1820 to 1840. From the capital at Hué, he implemented an extensive building program, which included construction of his own funeral complex in the southwest corner of the city. Set along the Perfume River, the burial site comprises 40 structures, including a building for the emperor’s clothes, pavilions for mourners, and the tomb itself. The bright colors, elaborate ornamentation, and lacquered finishes on the buildings contribute to the site’s elegance and beauty. After the king’s death in 1840, a group of guards was entrusted with the task of watching over his body and caring for the gardens. Unfortunately, this built-in maintenance program disappeared after the country divided and the monarchy was abolished. The city of Hué was badly damaged during the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive in 1968. By the 1990s, only 20 of the 40 structures remained, and those that survived were in need of significant repair.

1996 and 2000 World Monuments Watch

WMF placed Minh Mang’s Tomb on the Watch in 1996 and again in 2000. Working with the Thua Thien-Hué Provincial Peoples Committee and the Hué Monuments Conservation Center (HMCC), WMF developed a pilot conservation project for one of the structures, the two-story Minh Lau pavilion. Three terraces rise gradually around the pavilion, paved with green and yellow glazed bricks and planted with flowers. Four staircases approach it, each flanked by stone dragons. High humidity had caused a multitude of structural issues: the building materials were failing, termites had infested the wood, and fungus was growing quickly. The pavilion was dismantled and repaired from the foundations up. The floor, ceiling, and columns between were restored and moisture-proofed. Since 1997, WMF has also supported the restoration of several other structures on site, including the Stele Pavilion, Hien Duc Mon Gate, and Ta Tung Tu building. Environmental conditions had weakened the structural integrity of the buildings and damaged the decorative elements that defined the site. After documenting existing conditions, WMF supported restoration of the walls and roofs, the characteristic green yin-yang tiles, and the foundations where necessary. Waterproofing treatments were applied throughout to ensure the sustainability of the restoration work.

Minh Mang’s tomb draws 500,000 visitors annually—around 350,000 Vietnamese and 150,000 international tourists. The site was always intended to double as a tomb complex and national park, with landscaped gardens, terraces, lakes, and bridges that surround and connect the buildings. The plan for the burial site was dictated by geomancy, a form of divination using natural elements, because it was thought that the placement of the emperor’s grave could affect the fate of the entire dynasty. The tomb also functioned as a link between this life and the next, and thus Minh Mang’s burial site was arranged in the shape of a womb, representing Mother Earth and rebirth in heaven. This colorful landscape is an important national monument, continuing to educate visitors about the country’s history and culture.