Shwe-nandaw Kyaung

Shwe-nandaw Kyaung dates to the mid-nineteenth century. Believed to be originally part of the royal palace at Amarapura, it was moved to Mandalay and, with the name Mya Nan San Kyaw, became part of King Mindon-Min’s apartments at Mandalay palace complex. In the 1880s, soon after the King’s death, his son King Thibaw moved the structure to its present location, refurbishing it as a monastery. Significantly, the moving saved the building from the bombing of Mandalay during World War II, which destroyed most of the buildings of King Mindon-Min’s palace. The relocated Shwe-nandaw Kyaung is the only surviving wooden structure of that complex, featuring a unique gilded interior with extensive and intricate woodcarvings, unrivaled in their intricacy. In fact, Shwe-nandaw Kyaung is considered one of the most beautiful monasteries in Myanmar, and it is also one of the highest visited tourist sites in the country.

Wooden monasteries were once ubiquitous features of Myanmar’s landscape and important aspects of the country’s cultural heritage. Each village had its own monastery with variations in appearance and ornamentation that reflected local vernacular styles. However, many of the teakwood monastic buildings in Myanmar are endangered due to lack of maintenance or unsympathetic restorations, an issue emphasized by the rareness and high cost of teak wood and the loss of craftsmanship.

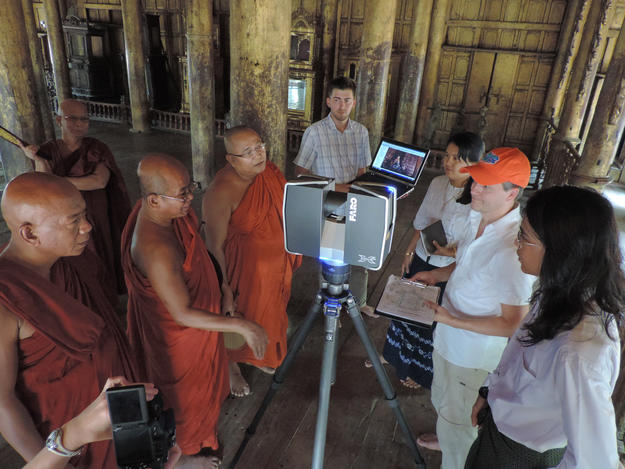

Collaboration between US Embassy and local heritage authorities brings training and conservation opportunities

With support from the U.S. Embassy in Burma, the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, and others, World Monuments Fund has been leading conservation efforts at Shwe-nandaw Kyaung since 2014. The project aims to preserve the nineteenth-century architecture and craftsmanship characterizing the original structure at the time of its 1883 re-construction in the present location. This involves deployment of building technologies and crafts unique to this monument.

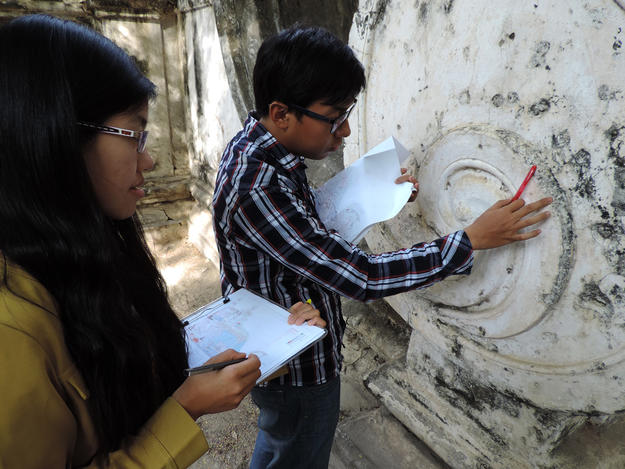

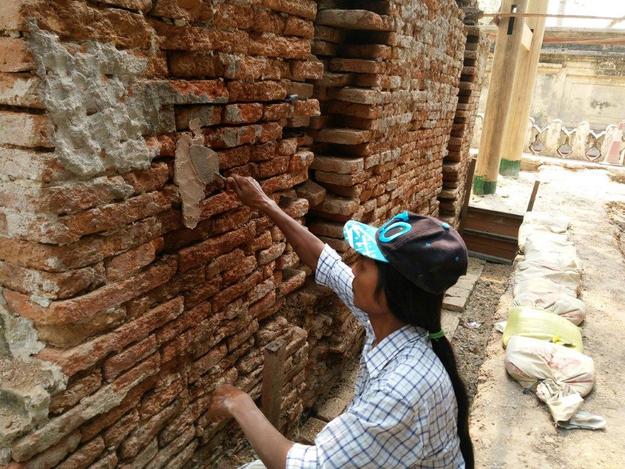

Extensive study was undertaken on the traditional building technologies employed at the site and an understanding of the deterioration and threats to the building’s primary building material, teak, in a tropical environment. Based on these activities, emergency structural, foundation, and drainage repairs were undertaken. Subsequent work focused on water management upgrades, repair of the monument’s staircases, and a comprehensive program targeting the monastery’s veranda—a first floor-level walkway surrounding the building.

Work is ongoing along with opportunities for training workshops on conservation practice and site management, and an important training program on traditional carpentry crafts and traditional timber framing, with a special emphasis on water damage and protective measures against fire. A cadre of skilled craftsmen are being trained in the forgotten Konbaung Dynasty on timber framing and carpentry techniques, creating a workforce that could be employed in other conservation projects implemented in the numerous historic wooden buildings scattered throughout Myanmar.

Videos