Conservation Projects

World Monuments Fund has partnered with many public and private, local and international institutions to safeguard and advocate for the preservation of Mexican heritage. Thanks to these partnerships, WMF has been privileged to work in many different places, from World Heritage sites to small religious buildings in remote rural locations. Although the aims and scope of each conservation project have varied greatly, WMF has always paid special attention to the stakeholders of each place, striving to contribute to their engagement and appreciation of the site in order to assure its long-term conservation and maintenance.

Heritage Advocacy

Since the creation of the World Monuments Watch—WMF’s main advocacy program—in 1996, thirty-six Mexican sites have been included. Nineteen of those sites became WMF field projects; for many other sites, the inclusion on the Watch was catalytic, helping bring national and international attention to the threats they face.

As founding sponsor of the World Monuments Watch, American Express has worked with us for over 20 years to preserve cultural heritage. An unwavering supporter of World Monuments Fund and our mission to safeguard the most treasured landmarks around the globe, American Express has helped preserve over 150 sites in 70 countries. In Mexico, American Express has contributed more than $1.8 million dollars to over a dozen conservation projects at some of the country’s most iconic sites.

Jesús Nazareno Church in Atotonilco

A masterpiece of Mexican Baroque architecture and a World Heritage Site since 2008, the church of Jesús Nazareno in Atotonilco was included on the inaugural Watch in 1996 to call attention to the deteriorated state of the sanctuary. For the next twenty years, WMF worked with local partners to restore the building thanks to the support of the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, American Express, and other donors.

The conservation works included the restoration of the sanctuary’s façade, the restoration of eleven chapels, and the conservation of three stone altars located in the main nave. These works contributed to preserving the building’s most famous feature, the series of murals by Miguel Martínez de Pocasangre, which reflect a blend of Catholic iconography and native religious beliefs.

Antigua Ciudad Guerrero (Guerrero Viejo)

After the construction of the Falcon Dam in the 1950s, the old city of Guerrero in Tamaulipas was flooded, and a new Guerrero was built. The old city had been founded in 1750 as “Revilla,” its layout following the Spanish Laws of Indies, which included a main square and streets built in a rectilinear grid. In the 1820s the town changed its name to honor one of the key figures of the Mexican War of Independence, Vicente Guerrero, who would later become President of Mexico.

From 2001 to 2004, through the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Conserve Our Heritage, WMF helped the former neighbors of Guerrero Viejo in their efforts to preserve the remaining structures of the town, accessible only during the dry season. The project included the stabilization of the remains of several eighteenth-century structures, as well as the adaptive reuse of two of them to serve as a guard station and visitor center.

Yaxchilán Archaeological Site

Yaxchilán, a classical Mayan urban complex, flourished between the fifth and the seventh centuries AD. The city was surrounded by the Lacandon forest and shaped by the Usumacinta River, which formed a natural border between Yaxchilán and its rival city of Piedras Negras in present-day Guatemala. Erosion, groundwater, looting, and the effects of tourism were seriously compromising the conservation of the ruins, which were included on the Watch in 2000 and 2002.

With support from the Selz Foundation, the Butler Fund for the Environment, and Fomento Cultural Banamex, WMF collaborated on the preservation of Yaxchilán, developing a comprehensive management plan for this significant archaeological site.

Modern Mural Paintings

After a massive earthquake struck Mexico City in 1985, WMF collaborated in the restoration of three mural cycles that had been terribly damaged: the murals at the Secretariat of Public Education by Diego Rivera, the paintings of the Church of Jesús Nazareno by José Clemente Orozco, and a mature work by Rivera at the Autonmous University of Chapingo.

In 1996, the modern murals of Mexico City were included on the inaugural Watch to help increase awareness about the significance and necessary conservation of these masterpieces. Thanks to the support of Friends of Heritage Preservation, American Express, and the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, WMF collaborated in the restoration of the astonishing Feast of the Holy Cross by Roberto Montenegro, painted in the former San Pedro y San Pablo convent of Mexico City.

Teotihuacan Archaeological Site

The city of Teotihuacán was built between the second and the seventh centuries AD. At its peak, it had a population of more than 200,000 people, rivaling many of the largest cities of European antiquity. This vast city, the largest pre-Hispanic site in the Americas, was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987.

Teotihuacán was included on the Watch in 1998 and 2000, and in 2004 the Temple of Quetzalcoatl was included individually because of its state of extreme deterioration. With the support of the Selz Foundation and American Express, WMF worked at the city for over a decade, collaborating significantly in the conservation of the Quetzalcoatl temple, and in the conservation of the iconic mural paintings at Tepantitla.

Santo Domingo de Guzmán

The convent of Santo Domingo de Guzmán was founded by Dominican missionaries in the second half of the sixteenth century. Built in the Spanish-Renaissance style and covering an entire city block in Tecpatán, the complex was one of the most important convents established by the Dominicans in the Zoque region. The building was abandoned in the nineteenth century and it was not reoccupied until the 1950s.

From 2004 to 2008, WMF collaborated with a local non-for-profit to develop a conservation plan for the convent, supporting the restoration of its south wing thanks to the support of the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage. Works in the convent have continued since, and it is expected that it will eventually house a community center, a museum, a library, visitor facilities, a crafts center, a hotel, and a restaurant.

Palace of Fine Arts

The Palace of Fine Arts was designed in the Art Nouveau style by Adamo Boari to commemorate the centenary of Mexico’s independence (1810-1910). However, the construction works were not finished until 1934, and its interior was therefore decorated with Art Deco motifs and an astonishing series of modern murals by Rivera, Orozco, Alfaro Siqueiros, and Montenegro.

The building, located within the boundaries of the Historic Center of Mexico City World Heritage Site, was included on the 1998 Watch to raise awareness about the structural problems that were allowing water to penetrate through the roof and damage the precious murals. Thanks to the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage and American Express, WMF contributed to the restoration of this masterpiece of Mexican architecture.

Madera Cave Dwellings

A group of sculpted clay dwellings nestled in the caves and cliffs in Chihuahua’s western Sierra Madre can be found in the region of the Huapoca Canyon, west of Ciudad Madera. The structures were created by the Paquimé or Casas Grandes culture between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries. The dwellings were later occupied by Apache tribes in the seventeenth century.

The Madera Cave Dwellings were included on the Watch in 1998 and 2000 to highlight the progressive decay stemming from years of natural erosion, neglect, and vandalism. With support from the J.M. Kaplan Fund and the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Conserve Our Heritage, WMF carried out several conservation, documentation, and research projects at the sites from 2002 to 2013. The works proved to be catalytic and additional conservation works were undertaken in neighboring caves.

San Miguel Arcángel in Mani

The Franciscan convent of San Miguel Arcángel in Mani was built in the second half of the sixteenth century. The complex included a hospital, an open-air chapel, the first school for indigenous people in the Yucatan Peninsula, and a church featuring one of the best-preserved collections of popular altarpieces, sculptures, and mural paintings created in Mexico during the colonial period.

Starting in 2003, thanks to the support of the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage and Fomento Cultural Banamex, WMF assisted in the restoration of the church, which was threatened by water infiltration and cracking problems. In addition, WMF collaborated on the adaptive reuse of the convent as a museum of Yucatec embroidery, to display a collection of pieces that represent the different techniques employed by the embroidery crafts tradition—the most important cultural expression of Maní.

Fundidora Park

The Compañía Fundidora de Fierro y Acero in Monterrey, founded in 1900, was for many years the leading steel-producing company in Latin America. After shutting down in 1986, the large foundry complex began its transformation into a public park. In 2001, it was declared an Industrial Archaeological Museum. However, despite its success as a public venue, the conservation of the numerous remnants of this large complex is very challenging.

In 2014, Fundidora Park was included on the Watch to highlight the need to preserve this important site. Through an award from American Express, WMF collaborated in the conservation of the blast furnace “Horno Alto No. 3”—today a science and technology center managed by a nonprofit organization known as horno3.

Apostle Santiago Church in Nurio

From 2000 to 2004, thanks to the support of the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Conserve Our Heritage, WMF collaborated on the restoration of the Apostol Santiago Parish Church in Nurio. This small temple was part of a hospital complex, or huatápera, founded in the sixteenth century by humanist Vasco de Quiroga. Following the ideas of Thomas More’s Utopia, the huatápera was the place where the indigenous people were taught religion, crafts, and the basics of self-government.

Quiroga recognized the rights of the indigenous people and in fact the techniques used for the construction and decoration of the church are a blend of Spanish and pre-Hispanic traditions. For instance, the coffered ceiling was built in the Spanish Mudejar manner, but painted with an indigenous technique. WMF supported the restoration of the ceiling, as well as that of the mural paintings, portals, and altarpieces within the temple.

Ruta de la Amistad

Ruta de la Amistad (Route of Friendship) was conceived as part of the legacy of the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. It included twenty-two sculptures—designed by international artists representing five continents—scattered along a 10-mile route that connected several Olympic venues. After the games the sculptures were neglected and engulfed by the growing city. Some of them were slated for demolition for the construction of an elevated highway.

Local advocates have been hard at work to rescue and restore the sculptures. Ruta de la Amistad was listed on the 2012 Watch to raise awareness about the significance of this public art project and encourage preservation of the remaining sculptures. An award from American Express contributed to the restoration of two of the sculptures and supported several public engagement activities, including a Watch Day with over 1,500 participants.

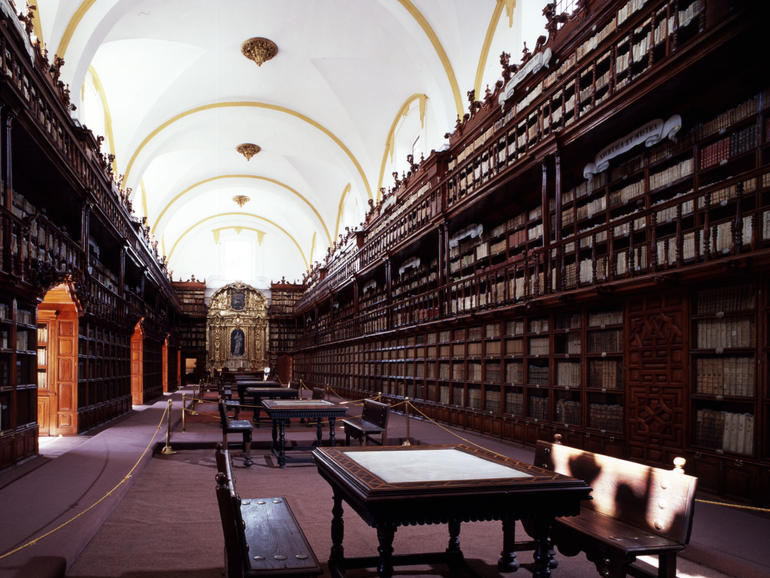

Palafoxiana Library

In 1646, Bishop Juan de Palafox y Mendoza donated 5,000 books to the Seminary of San Juan in Puebla under the sole condition that they be made available to the public. This act of philanthropy led to the foundation of the first public library in the Americas. In 1773, Bishop Francisco de Fabián y Fuero ordered the construction of a magnificent edifice to house the Palafoxiana Library in the city of Puebla. The library, along with the Historic Center of Puebla, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987.

Following a devastating earthquake in 1999 that resulted in considerable damage to the building, WMF collaborated in the stabilization of the structure and the restoration of the extraordinary baroque bookcases, the Virgin of Trapana Altar, and the original clay and Talavera floors. The work was made possible through support from the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage and Fomento Cultural Banamex.

San Francisco de Tzintzuntzan Convent

The San Francisco Convent in Tzintzuntzan—begun in 1525 and completed 71 years later under the direction of Vasco de Quiroga, the first bishop of Michoacán—was the first Franciscan mission in New Spain, founded for the conversion of the indigenous population to Catholicism. Bishop de Quiroga repurposed the convent into a large hospital complex (huatápera), and transformed the convent church into the first cathedral in the region.

The 2004 Watch called attention to the damage caused by years of weather exposure, lack of maintenance, and earthquakes at the Tzintzuntzan complex. With funding from American Express and the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, WMF supported the stabilization of several parts of the convent that were under great risk of collapse. The works promoted public interest in the building, and funds were allocated to adaptively reuse it as a museum and community center.

San Juan de Ulúa Fort

The construction of the San Juan de Ulúa Fort in Veracruz started in 1535 and continued for over three centuries. A significant stronghold in the coastal defense system of the Spanish West Indies, the complex included a governor’s palace, several towers, dungeons, parade grounds, and a cemetery, among other facilities.

Centuries of exposure in a highly polluted and busy harbor caused great deterioration to the fort and led to its inclusion on the Watch in 1996, 2000, and 2002. In 2002, through an award from American Express, WMF supported restoration works and the creation of new facilities for the museum and cultural center, which the fort currently hosts.

Mexico City Historic Center

The Historic Center of Mexico City, a World Heritage Site since 1987, was included on the 2006 Watch in an effort to highlight the numerous preservation challenges it faces. The area, which contains Aztec remains dating back to the fourteenth century, was built primarily under Spanish rule, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Today, infrastructure problems, pollution, and overcrowding present serious challenges for the preservation of the historic center.

Thanks to the support of the Fundación del Centro Histórico, the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, and American Express, WMF initiated a program to revitalize the neighborhood in collaboration with local partners. As part of this project, the Neoclassical building El Rule is being transformed into a visitor and education center to promote economic development through sustainable tourism management.

Yucatán Indian Chapels

The Indian Chapels in the Yucatán region were built by Spanish missionaries to facilitate the evangelization of indigenous people living in remote areas. These chapels worked as outposts of larger missions, and they were usually known as “visiting chapels,” as a priest would visit them periodically to perform mass and other rites.

Most of the chapels were abandoned in the nineteenth century, and either demolished or inadequately restored during the following decades. In 1996, the chapels were collectively placed on the inaugural Watch to call attention to the challenges they faced. With support from American Express, WMF developed a pilot restoration project at the Tibolón chapel. The project, carried out by local communities using local materials, served as a model for the restoration of other Indian chapels in the region.

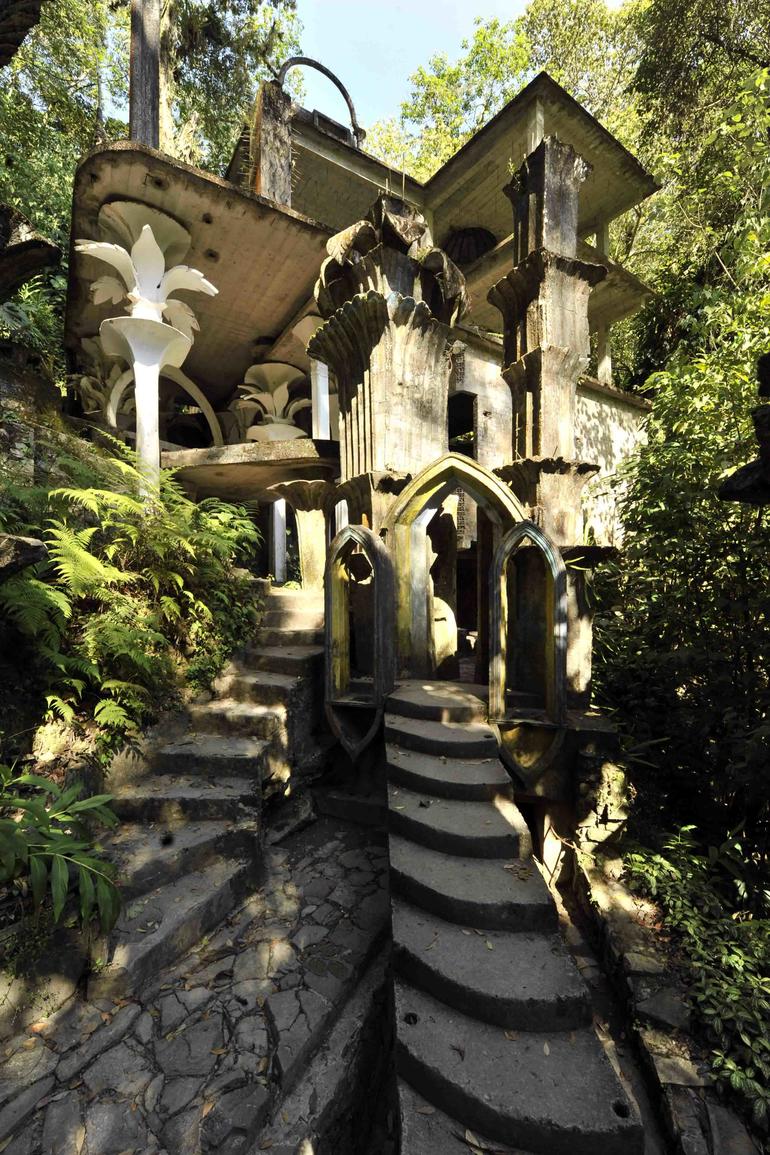

Las Pozas

In the late 1940s, wealthy British poet and patron of surrealist art Edward James purchased an eighty-acre subtropical rainforest estate in San Luis Potosí. For the next forty years, James collaborated with Plutarco Gastelum and local artisans to design and build a series of canals, pools, and architectural follies scattered throughout the property. After James’ death in 1984, the jungle grew uncontrollably, affecting many of the picturesque structures.

Inclusion of Las Pozas on the 2010 Watch called for immediate actions to prevent further damage. With funding from the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve our Heritage, Friends of Heritage Preservation, the Kress Foundation, and Fundación Roberto Hernández Ramírez, WMF supported the restoration of James’ cabin and the conservation of the so-called House With Three Stories That Might Be Five. Additionally, a series of interpretive displays were created to enhance the visitor experience at the site.

Santa Prisca Parish Church

The Church of Santa Prisca was built in the 1750s by José de la Borda, after he discovered a silver mine in his property. Paradoxically, the vibrations caused by mining blasts, combined more recently with automobile traffic and seismic activity, are among the main threats to this eighteenth-century masterpiece of Mexican Baroque architecture. In order to raise awareness about these threats, the temple was included on the 2000 Watch.

Thanks to the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, American Express, Fomento Cultural Banamex, and the Fundación Roberto Hernández Ramírez, WMF carried out restoration work on the exterior and interior of the church—as well as on the pieces of art within the church—over a period of fifteen years. Along with the main temple, several ancillary structures were also restored. A bilingual publication about the complex and its restoration was published in 2016.

Colonial Bridge of Tequixtepec

This 450-year-old bridge, located between the once-flourishing cities of Coixtlahuaca and Tequixtepec, was built as part of a route that connected several Dominican convents in the region of Oaxaca. The bridge was made of volcanic tuff by indigenous workers, who carved pre-Hispanic motifs in the stones.

The bridge was included on the 2012 Watch to raise awareness about the structural deterioration that recurrent floods in the Coixtlahuaca basin were causing, putting the bridge in danger of collapse. Soon after its inclusion, public funds were allocated for the conservation of the bridge, including its stabilization, restoration, and 3D-scanning.

Monte Albán

Monte Albán archaeological site, an ancient Zapotec city built from 650 to 800 A.D., was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987. Despite its international recognition, the site faces many threats, ranging from a lack of tourism management to erosion, forest fires, looting, and vandalism. The inclusion of Monte Albán on the 2008 Watch helped raise awareness about these threats, and especially about the accelerated decay of numerous stelae, or stone markers, with valuable Zapotec inscriptions.

With support from the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Preserve Our Heritage, WMF developed a project, in partnership with local institutions, that focused on the conservation, documentation, and interpretation of the carved stones. Many of the stelae were salvaged, and laboratory and storage facilities were built in order to facilitate their long-term conservation and protection.

Chapultepec Park

The Chapultepec area has been used as a park since pre-Hispanic times, when it served as a place of retreat for Aztec rulers. Since then, Aztec, Spanish, and modern Mexican artists, designers, engineers, and landscape architects have shaped this unique site. Today, Chapultepec Park contains nine museums, a zoo, an amusement park, and an extensive variety of green recreational spaces, welcoming approximately 15 million people each year.

This historic public space was included on the 2016 Watch to support the ongoing efforts to restore the park’s environmental balance, functionality, and beauty. With generous support from American Express, WMF is working alongside the Chapultepec Trust in the restoration and adaptive reuse of the former nineteenth-century gatehouse building at the park, which will be converted into a museum and orientation center for visitors.

WMF’s long history of conservation projects in Mexico has been possible thanks to our local partners and generous donors including American Express. Our commitment to the country’s heritage, which began shortly after the devastating earthquake of Mexico City in 1985, has strengthened continuously ever since. Through our activities at these heritage sites, our hope is that at the conclusion of each project, the public has the opportunity to better understand how a historic site enriches the lives of the local communities and visitors.